“There were 694,000 incidents of violence at work in 2017/18. That’s the equivalent of more than one violent incident a minute.”

It’s easy to agree that violence at work is never acceptable and should not be tolerated, though statistics show that UK workers face an alarming amount of violence on a daily basis.

While violence is more prevalent in certain industries it is a concern for all workers, particularly those in public-facing roles. For example, those working in protective service occupations such as police officers and security guards face the highest risk of assault and threats, at 11.4%, while health and social workers have a risk of 5.1%, more than three times higher than the average risk of 1.4%.

In this paper, Safepoint will explore the reality of violence against workers in the UK, discuss the nature of lone working and consider some ways in which employers and lone workers can avoid violence while at work.

When you imagine someone working alone, you might think of healthcare staff tending to patients on a night shift, farmers operating tractors or long distance drivers delivering vital goods and services. But look closer and you’ll find lone workers operating in almost all industries and employed by a wide variety of organisations.

Lone workers are a significant and integral part of the UK economy. Over 20% of the UK’s workforce – more than 6 million people – explicitly identify as lone workers, though the number of people who work alone for extended periods is likely to be many more.

The Health and Safety Executive (HSE) defines a lone worker as:

“Someone who works by themselves without close or direct supervision. Lone workers include those who:

Keep in mind that a lone worker does not need to spend their entire day working alone to be considered a lone worker. More people than you think spend significant portions of their working life as a lone worker: think of the electrician who might enter a property to implement repairs alone or the receptionist left alone for long periods in a large office building.

As employment law, HR and Health and Safety Service organisation Croner note, a lone worker can be considered: “a worker whose activities involve a large percentage of their working time operating in situations without the benefit of interaction with other workers or without supervision.”

Both the HSE and Croner definitions are used by numerous worker unions. With these definitions, we can see that a large number of people qualify as lone workers for significant portions of their working day: consider security staff who may work in groups in a control centre but perform solo security patrols or construction workers who may work on a busy site though perform certain high-risk tasks alone.

Employees and employers cannot afford to discount these workers and only by correctly identifying those lone-working staff can you begin to improve lone-worker safety.

“Protective service occupations are at the greatest risk of violence, with the rate of violent assault or threat 8 times the average rates of 1.4%.”

Lone workers occupy a large number of roles in industries across the world economy. Here are a few examples of lone workers sorted by industry.

There were 694,000 incidents of violence at work 2017/18; that’s the equivalent of more than one violent incident a minute in the UK.

One in eight people have experienced violence at work – with over 31 million people in some form of employment in the UK, this means that as many as 4 million people have experienced violence at work during their career. Furthermore, 20% of those people who reported violence also report it happening more than 10 times.

According to a survey conducted for the Suzy Lamplugh Trust, 81% of lone workers are concerned about violence and aggression and one in ten of those surveyed had been punched, kicked, or suffered some other form of violent attack.

In many sectors, instances of violence against lone workers is rising. In the retail sector, a 2016/2017 survey conducted by the BRC showed that violence and abuse against lone working staff was up by 40% on the previous year.

As these statistics show, the true extent of violence at work is staggering. Violence against lone workers is a very real issue that can result in long term physical and psychological harm to employees, altering the course of people’s lives for years to come. Violence should not be tolerated, whatever the role or organisation.

Identifying the risks to lone workers in your organisation is the first step towards lowering the risk of violence and improving lone worker safety.

“82% of those people committing violence against lone workers were strangers or members of the public known through work”

This list is by no means exhaustive and your particular organisation and lone workers will see issues specific to your industry, location, personnel and business.

Protective service occupations – including police officers, firefighters, fire inspectors, correctional officers and bailiffs and security guards – are at the greatest risk of violence, with the rate of violent assault or threat 8 times the average risk of 1.4%. Health and social care specialists have a 5.1% risk of violent assault or threat, and health professionals have a rate of 3.3%. Other roles with higher than average risk include managers and proprietors, with a 2.3% risk of violence. Transport and mobile machine drivers and operatives, sales occupations, and leisure, caring and other service occupations all saw rates of risk above the 1.4% average.

The risk of violence to lone workers is predominantly seen in interactions with or exposure to the public: 54% of those people committing violence against lone workers were strangers. 28% were clients or members of the public known through work. 9% of violent acts were committed by a colleague or workmate. If your lone working staff are interacting with, or are exposed to the public in any way, whether they are salespeople, maintenance staff or foresters, they are at potential risk of incident.

Think carefully about how lone workers across your organisation interact with the public and how certain factors can increase this risk: working without proper training, equipment or without a clear procedure in place can turn a potentially violent incident into an assault.

“Despite the high rates of violence and aggression, fewer than 18% of respondents had received personal safety training in person or online, only 34% knew of a written personal safety policy.”

In the HSE’s 2018 report on violence at work, 41% of incidents resulted in physical injury including bruising, cuts, scratches, broken bones, stab wounds, concussion and loss of consciousness. These kinds of physical injuries are unacceptable, and should never tolerated by lone workers or their employers as being part of the job.

Beyond physical injury, the consequences of violence at work can include increased staff turnover, lost working hours, absenteeism, counselling costs, declines in mental health, decreased staff morale, reduced quality of life, damage to organisational reputation and even fines and liability. Physical injury is not the only measure of violence against lone workers. The emotional consequences of workplace violence can result in long lasting and severe damage to people’s mental health which have far reaching effects for both individual workers and employers.

Violence in the workplace has long been associated with reduced productivity – lone workers who have been the victims of violence are often plagued by feelings of anxiety or fear and they are also more likely to be absent from work than those people absent for reasons of ill health.

Medical Xpress report victims of violence in the healthcare sector suffer from post-traumatic stress (between 5% and 32% according to four studies), increased vigilance, irritability, and sleep disorders and up to 60% of victims considered leaving their jobs.

Findings from the Fifth European Working Conditions Survey indicate that absence rates due to work related ill health are significantly higher among those exposed to different forms of workplace aggression. Specifically, a higher proportion of workers exposed to physical violence were absent for 10 or more days due to work-related ill-health in the EU. (28% vs. 15%).

From these statistics, it’s clear that violence against lone workers has dire consequences for both lone workers and the organisations employing them. Beyond the legal obligation companies have to safeguard their staff, they also have a moral and ethical responsibility to keep lone workers safe from violence wherever possible.

Reducing the risk of violence is a shared responsibility between the lone worker and their employer. No single solution is enough and by putting in place a multifaceted approach; considering working environment, personal behaviour, job design, tools, procedures and policies, you can be best positioned to avoid violence as a lone worker.

Sadly, some lone working roles will always have a potential for violence: employees in security and protective services or those working in social care with vulnerable clients or people who may be under the influence of drugs or alcohol will always have a risk of violence. Potential for violence does not mean that violent incidents are unavoidable or that they should be tolerated. There are ways to reduce risk and prepare for violent incidents effectively and stay safe as a lone worker.

As Unison’s “It’s Not Part Of The Job” campaign clearly articulates, no workers should have to accept violence as part of their work and we can do more to minimise and prevent violent incidents.

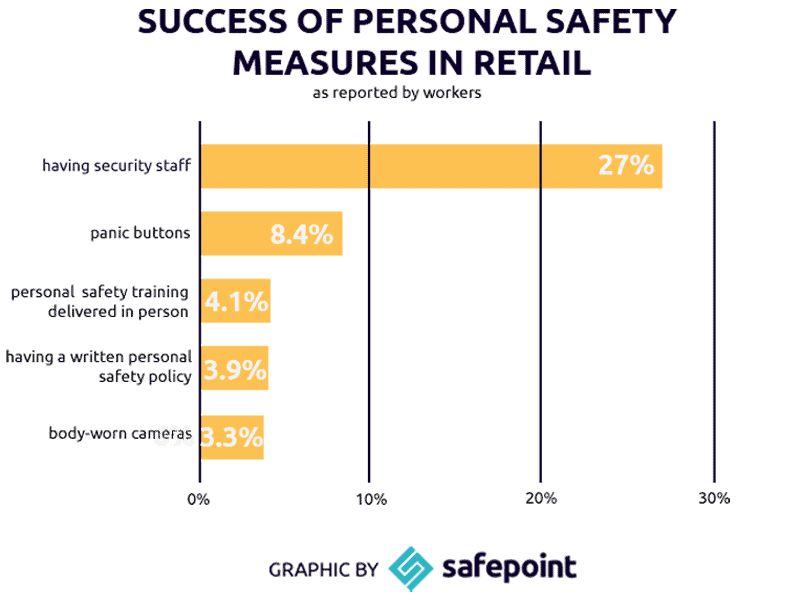

As a survey of retail workers conducted by the Suzy Lamplugh Trust found: “Despite the high rates of violence and aggression, fewer than 18% of respondents had received personal safety training in person or online, only 34% knew of a written personal safety policy and fewer still (21%) knew of clear reporting procedures for personal safety incidents.” This is simply not good enough, and employers need to step up in reducing the rates of violence against workers by taking some simple, practical steps.

At Safepoint, we want to help. Here are some of the key ways employers and lone workers can help prevent workplace violence.

“In many of the Health and Safety Executive’s case studies, they found that ensuring staff were friendly, polite and courteous was effective in reducing violence at work.”

Training lone workers on how to deal with violence and aggression should be one of the first steps any organisation with lone workers should take in preventing assaults and threats of violence at work.

Being trained in how to engage successfully with the public and cultivating a customer service centric attitude is something all workers who interact with the public should be given. It’s not enough for utility workers to simply know how to conduct repairs – interacting with customers is part of the job and knowing how to detect and defuse potentially violent situations will not only help prevent incidents but also improve customer satisfaction. Everyone’s a winner.

A lesson in empathy: learning to understand how certain situations can become a source of aggression and empathising with the customer’s position. If an engineer is late to perform crucial repairs the customer may be understandably frustrated. Empathising with, rather than escalating these situations isn’t just good customer service, it’s a key part of reducing the risk of violence at work.

Awareness: knowing how to identify aggression in others, identify situations in which the risk of violence might be elevated and develop methods of responding calmly and authoritatively. For example, learning how to ascertain when a customer is becoming frustrated and verbally aggressive can help staff respond appropriately, by listening and answering positively and authoritatively, rather than responding in kind.

Cultivating self awareness is also an important part of this kind of training. Lone workers need to know how to identify when they are frustrated or exacerbating the situation and have methods for stepping away, taking a moment to think and come back to a situation with a clear head.

“Zero tolerance policies and campaigns aimed at making it clear to customers that violence and harassment is unacceptable and illegal can also help reduce violence.”

Walkers TV, Radio and Music Centre Ltd in Wales found that they could improve customer service and staff safety at the same time. They ensure that, “staff are well trained in customer service skills. This helps to minimise incidents involving angry and frustrated customers. It is company policy that customer problems are dealt with quickly, calmly and positively to avoid the problem escalating.”

Developing strong customer service skills in all lone working staff, even those who are not in sales can be hugely helpful in preventing potential violence. If your delivery and maintenance staff are trained to deliver good service and understand that they are presenting the company at every opportunity, they too can keep customers from getting frustrated. In many of the HSE’s case studies, they found that being friendly, polite and courteous were effective measures in reducing violence at work. These tools should be used by all your lone workers, regardless of department or role.

Good customer service means customers, service users and members of the public are less likely to become frustrated or angry and situations are less likely to escalate. A positive, empathetic and service focused attitude towards customers, clients and service users costs nothing and can not only generate income and goodwill but can help safeguard your staff too.

If you do not have the in-house expertise, consider bringing in an outside organisation to teach violence prevention. The cost of any such training is easily outweighed by the prevention of injury, potential staff absence, incident management, and potential liability.

In short, a risk assessment is a process of identifying, measuring and evaluating risk for individuals, organisations, assets and the environment as a result of a particular activity, role or undertaking.

If you were starting an industrial maintenance company and your workers were going to be working on factory sites, your risk assessment would be conducted to see all the risks they might face while working on those sites.

A lone worker policy is a document that sets out your companies rules, best practices and guidance for working alone. It will help new and existing staff understand the risks to them and their organisation when lone working.

Broadly, your lone worker policy will include findings from your risk assessments, industry best practice, practical guidance, legal obligations and other items that allow both lone working employees and employers to understand their responsibilities, work safely and legally, and know what to do in the event of an incident.

It’s a legal requirement to conduct risk assessments for your staff and highly recommended to have a lone working policy. They should both be considered part of your organisation’s toolbox and used accordingly. If they have been meaningfully and practically put together, your risk assessment and lone working policies can be key factors in reducing violence to lone workers and a point of call for all members of your organisation.

Your risk assessments should be written to cover all aspects of your organisation and the workers therein. Your risk assessment needs to be bespoke to your industry and to each role working role: cut and paste isn’t sufficient. Roles in housing associations, for example, are extremely varied, and the risks facing a lone worker conducting housing checks can be quite different to in-office staff or those conducting structural repairs.

Be certain to liaise with workers in all departments and at all levels: your workers on the ground may have insight that managers and board members do not. For example, a risk assessment may discover that taxi company drivers do not have sufficient training to deal with violent incidents, or that construction workers do not have the equipment to safely cordon and protect their workspace, exposing them to potential threats.

Your lone working policy is a comprehensive guide to lone working in your organisation and should be designed to give your employees guidance on working alone, as well as an understanding of best practices, tools, training and support available to them. If your employee has concerns about violence on the job, your lone working policy should be able to answer those questions and direct them to further support if necessary.

“Share information with local authorities, other businesses and security teams. Knowledge of incidents occurring in your area or industry can be invaluable in helping safeguard lone workers and preventing violence”

An internal knowledge base and log of persons or locations known to be dangerous can help lone workers better prepare for risk. Furthermore, you may find that certain jobs or locations would benefit from workers doubling up, or other measures put in place to help safeguard your staff. The environment agency, for example, are sure to have two people visit a site if it is deemed necessary. If the risk of violence is particularly high, they go as far as having the police escort inspectors.

Smart reporting and thorough incident reports are integral in first acknowledging and measuring the extent of violence in your organisation and then, having the necessary insight into resolving the situation.

Share information with local authorities, other businesses and security teams. Knowledge of incidents occurring in your area or industry can be invaluable in helping safeguard lone workers and preventing violence. A united community can also be a strong deterrent against violence: lone workers can feel less alone if members of your local business community are also looking out for them.

Solihull Metropolitan Borough Council’s Housing Services Division have a policy where “employees receive full support from their managers if they ‘walk away’ from a situation in which they feel uncomfortable or threatened.” It’s important to value your staff in a way that means lone workers will not jeopardize their personal safety while working alone and feel backed up if they make the decision to walk away from a potentially violent situation. For Solihull Council, this is considered the most successful form of violence prevention.

In sectors where cash or desirable goods are handled, consider changing the policy to ensure that cash is not left on site unnecessarily, improve security for those places and reduce potential exposure for those handling cash.

In retail, be sure to clearly display crime and violence prevention material – for example, table top displays, clearly signposted CCTV, posters and staff safety policies. In other sectors, ensure your clients and the public are clear on your policies on violence against staff by having material on your website, on your sites and in your public documentation. Deterrence can be a strong tool and by taking a visible stance against violence, you are doing your part as a socially responsible organisation. As Tuc notes, “Zero tolerance policies and campaigns aimed at making it clear to clients/customers that violence and harassment is unacceptable and illegal can also help.”

Improve security lines of sight and reduce the number of isolated areas where employees may have to work alone. In isolated areas, ensure that lighting and access is good and that proper security is in place for those isolated areas. If potential thieves cannot gain access to back office or warehouse areas then the risk of confrontation is reduced.

Ensure there is a means to communicate and stay in touch with other lone workers, support staff and managers. Clear lines of communication are integral, obviously in an emergency but also on a day to day basis. Ensure that staff are encouraged to get in touch if they need to and that you have someone they can reach, even if they are working out of regular working hours. A lone worker safety solution such as Safepoint can help ensure this contact, including an emergency alert and a silent alarm, so they can communicate a need for help.

“Report, record and document all incidents, big or small. Every incident or threat of violence is an opportunity to learn, improve and reduce the risk of recurrence.”

In addition to all the above, there are some specific elements of risk for remote or mobile lone workers that can be mitigated with proper care.

Ensure safe means of travel; whether this is between sites, to and from work or otherwise. For social care workers, this might mean providing taxis to and from locations, or providing provision for pick-up during late-hours.

If you’re a lone worker on foot use busy thoroughfares and well lit areas. Stay alert and be cautious; avoid the distraction of your phone or loud music where possible.

Ensure your lone workers have a clear idea of how you would exit a location in an emergency. If working in an individual’s home, lone workers should know where the exits are and be able to reach them, just in the event that a situation escalates.

Don’t advertise your personal belongings, and keep inessential belongings to a minimum. Leaving your laptop on the front seat of your parked car is an invitation to thieves. Do not give confrontations or incidents the opportunity to surface by removing the temptation.

Encourage lone workers to be cautious and to only proceed if they feel safe. Working remotely or mobile can result in liquid working conditions. Lone workers should be encouraged to conduct dynamic risk assessments and respond to the specific situations they find themselves in. Furthermore, they should be empowered to leave a job if they do not feel safe or if they determine the risk to their personal safety is too great.

Have a check-in system. If lone working staff do not check in at appointed times, you know there is an issue and they should be contacted.

Consider using a lone worker safety solution to monitor and safeguard staff in transit. Safepoint, for example, uses GPS data to give employers and guardians updated in real time. Visibility is integral in safeguarding and providing oversight and support to your lone workers in the field.

Report, record and document all incidents. This is not only a case of protecting yourself and your organisation legally by creating a safety audit trail and a record of incidents, but also a means of future prevention. Every incident or threat of violence is an opportunity to learn, improve and reduce the risk of recurrence.

You may discover that a certain role, location or service user has been a cause for repeated acts of violence and that you need to take steps to review those elements as an organisation. Perhaps staff need better equipment or certain areas need to be fitted with CCTV; you may even find that job design needs to be reconsidered.

Ensure you have the tools and systems in place to effectively record and learn from incidents. Consider a lone working safety solution which allows you to monitor, record and respond to incidents and emergencies as they occur. Safepoint records a data including GPS location, time/date, battery life, and more – all in real time. This data can be invaluable when it comes to post incident support.

Ensure you have post incident support in place for victims of violence. This can include counselling, wellbeing advice, job reviews and more. Such responses should include provision for both physical and mental wellbeing and be continually reviewed with the best of your lone workers in mind. Managers should also be trained and encouraged to look for signs of post traumatic stress disorder. Post incident support is essential in keeping your lone workers happy, productive and healthy.

Violence at work is a reality for too many lone workers in the UK. At Safepoint, we believe more can be done at every level to lower these appalling figures. Understanding the risks and causes of violence is your first step in safeguarding your lone workers.

With a combination of awareness, training, support, policies, and the right tools, you can lower the risk of violence for your lone workers and give them the confidence and protection to do their jobs effectively and without the additional pressures a fear of violence can bring. This document should be considered a starting point: the risks to lone workers are ever changing and so too, should the response.

A lone worker safety solution like Safepoint is your partner in delivering effective worker safety and in safeguarding your business in the event of an incident. Try our lone working solution to see how our simple, easy to use platform and app can help your lone workers stay safe.

Award-winning safety management tools and a fully accredited response team.